Of all Third Culture Kids (TCKs), Freddie Mercury is certainly the most famous. Everything about the man screams Rock Star– his outrageous outfits, his incredible talent, and his well-documented sexual exploits. Everyone seems to focus on these parts of him, but there’s another thing not many people talk about- the fact that he choose his culture, and it wasn’t what he was born into.

“Freddie’s real name was Farrokh Bulsara. Whether it’s Persian or Indian or British — everyone’s going to claim him,” says actor Rami Malek, who played Mercury in a recent biopic.

Everyone might be claiming him, but who was the real Freddie Mercury?

First off, he and his family were Parsi (with roots in India), and were Zoroastrian by faith. He may not have practised the religion to the letter, but he did the important things: taking part in a Navjote ceremony at age 8 (a coming of age ritual similar to a bat mitzvah or confirmation) and insisting his funeral be in-keeping with Parsi tradition for his family.

He was born in the English protectorate of Zanzibar. Many have no idea he was not born ‘Freddie Mercury’- instead, his birth name was Farrokh Bulsara. He didn’t speak with an English accent until he was much older, because he wasn’t raised in England for the majority of his young life. If you listen closely in some interviews, the Indian part of his accent slips through; otherwise, you’d have no idea.

He went to St. Peter’s Church of England School, a prestigious English-style boarding school in Panchgani, India, just outside of Bombay. It was here where he gained the nickname, ‘Freddie’. The boy who went there was skinny, buck-toothed, and quiet; the exact opposite of the stage personality he would invent later. Classmates like Ajay Goyal had made no connection between Freddie and Farrokh until much later: ‘I’d heard of Freddie Mercury, of course, but I never made the connection with Farrokh. I only discovered it was him from our school alumni page a few years ago.’

Farrokh left St Peter’s shortly after discovering his passion for music (a passion that apparently caused his other grades to take a nosedive). He opted instead to finish the last two years of his schooling at the Roman Catholic St. Joseph’s Convent School back in Zanzibar, only to move again when his family fled revolution and persecution in 1964, moving to England when he was seventeen. Like most TCKs, Farrokh didn’t want to leave India or Zanzibar. He felt at home there, the culture was one he’d grown up with- the streets of London must have been a far cry from home when he first arrived. But, like many of us, he wasn’t going to stay down forever. There were opportunities in London, and Farrokh grabbed them with both hands.

He recieved a diploma in Art and Graphic Design from Isleworth College and Ealing Art College in England, sold second-hand clothes at the Kensington Market (where he actually met David Bowie) and held a job at Heathrow Airport. However, he never forgot the passion he picked up in boarding school in India: Music. The first songs he learned to play were Indian songs. In an interview with The Telegraph, Mercury’s mom said that “Freddie was a (Parsi) and he was proud of that.”

He went to lengths to hide his ethnicity, according to band member Roger Taylor, because ‘he felt people wouldn’t equate being Indian with rock and roll.’ Contemporary musicians and academics are inclined to agree with him.

Leo Kalyan, a queer British Pakistani-Indian singer-songwriter, says Mercury’s South Asian heritage is still not fully understood today: “because South Asians are still deliberately ignored within the Western music industry… (Freddie) didn’t talk about going to school in India or his love for Lata Mangeshkar (A Bollywood singer whom he adored). That wasn’t part of his narrative.”

However, it is a disservice to TCKs and Freddie himself to say he only became ‘Freddie Mercury’ to whitewash his identity. TCKs commonly adapt to the culture we’re in not only because there’s no choice, but because we’re strong enough to remember who we are inside and bring that to the culture we adopt. There is always a conscious choice when we become who we are- whether that’s assimilating, keeping to our home culture, or (more often) choosing what we take from each.

The ‘Mercury’ in his name apparently came from his music itself- fitting, considering how deeply ingrained it was to his personality. The final verse of the song ‘My Fairy King’ goes:

Someone, someone has drained the colour from my wings

Broken my fairy circle ring

And shamed the king in all his pride

Changed the winds and wronged the tides

Mother Mercury Mercury

Look what they’ve done to me

I cannot run, I cannot hide

“He said, ‘I am going to become Mercury, as the mother in this song is my mother,’” Guitarist Brain May said, “And we were like, ‘Are you mad?’”

Maybe. But maybe this was also part of Freddie’s process: carving a place in culture for himself. British culture wasn’t exactly a safe haven for queer people of colour (especially not after Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech)… but his own fairly conservative upbringing in various Christian schools and Zoroastrian faith condemned queerness- a core part of his identity. Perhaps, for Freddie, distancing himself from the non-Western part of him was synonymous with distancing himself from the hurt and shame associated with his sexuality.

May once stated, “I think changing his name was part of him assuming this different skin… I think it helped him to be this person that he wanted to be. The Bulsara person was still there, but for the public he was going to be this different character, this god.”

Freddie even included hints of his non-English heritage in his music: songs like Bohemian Rhapsody contain blink-and-you’ll-miss-it references, words like ‘Bismillah’ (Arabic, meaning ‘In the Name of God’). His family are quick to remind us how his non-Western identity influenced him: “I think what his Zoroastrian faith gave him,” his sister Kashmira Cooke explained in 2014, “was to work hard, to persevere, and to follow your dreams.”

However, like most TCKs, Mercury also didn’t fully identify with what he was born into. Drummer Roger Taylor once said, “Freddie talked to me about being Parsi-Indian and about his family. But it was all very private stuff. The Parsi culture was very different, and he felt that he wasn’t part of that culture. His mother was always wonderful to him, but he knew there was an immense gap in lifestyles.”

“Freddie was always into Western music but I think when you grow up in an Indian household that stuff sort of seeps deep into you,” said musician Pheroze Karai, “It’s blatant in songs like ‘Mustapha.’ Even when he’s just riffing live there was a combination of things where it could almost be a ghazal.”

There’s an infinite number of Freddie Mercury’s, and it all depends on who you speak to, what culture they’re from, etc.

In the Rami Malek movie, you get the idea that becoming British was a no-brainer for Freddie, that his family wouldn’t accept him the way they accepted Farrokh. In-film, his father snaps, ‘now the family name’s not good enough for you?’

But perhaps this is looking at things the wrong way. There wasn’t anything wrong with Farrokh Bulsara, apart from that wasn’t who Freddie was. Like many of us TCKs, Freddie hopped continents as a kid and took little things from each culture, but every piece went towards the same person: Freddie goddamn Mercury. And there’s nothing wrong with that. If you say, ‘but he should have acted more Indian’ or ‘he was British, that’s the end of it’, you aren’t understanding the TCK experience, or even the immigrant experience.

“It’s interesting to see how much people still think he was a white British dude… Freddie Mercury is someone who transcended being just desi to more on kind of this world stage.” – Nadia Akbar, author of Goodbye Freddie Mercury

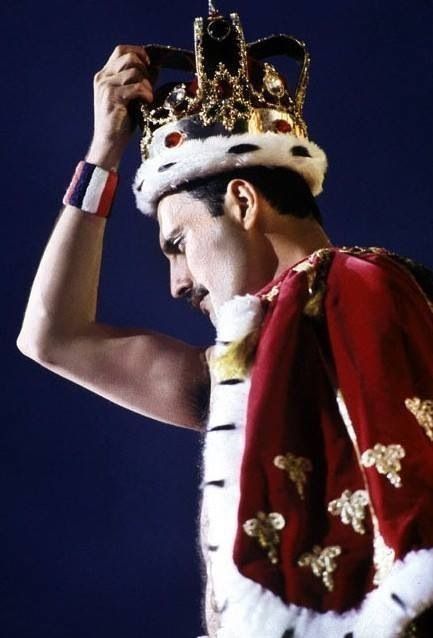

Today, we think of Freddie as a British National Treasure. He had the accent, dressed as our royalty, and constantly included our flag in his performances. At the same time as he exemplified Britishness, he was himself: a queer, South-Asian, Zoroastrian TCK who centred his life around music, resulting in iconic songs such as Bohemian Rhapsody, and the best-selling album in UK chart history: Queen’s Greatest Hits.

Maybe we should celebrate more of his whole cultural identity, rather than trying to claim him for one culture or another.